In this article, we’ll look at the subject of lengthy inbound messages, and some practical ways for bots to handle them better.

One of the many things we’ve come to notice and appreciate from working in the field of CAI, is that everyone naturally communicates in different styles. It’s a fascinating psychological aspect that exists within this area of work. When reviewing a long list of training phrases, it’s easy to overlook the fact that these are all the ways people can (and do) state exactly the same thing. There might be hundreds of variations that explain the need to check the status of an order, request a refund, or schedule an appointment .

One thing we’ve regularly seen is a characteristic that we’ve termed ‘long utterances’. This is where the customer provides too much information for the bot to handle effectively. There’s no benchmark figure for a ‘long utterance’, but we might consider inputs over 250 characters and comprising several sentences to fall into the long utterance category. We’ve seen older-platform bots that simply didn’t handle anything over 2000 characters and wouldn’t reply! There was an assumption in the technical architecture that no-one would ever write that much into a tiny chatbot window. But they do, in a variety of ways.

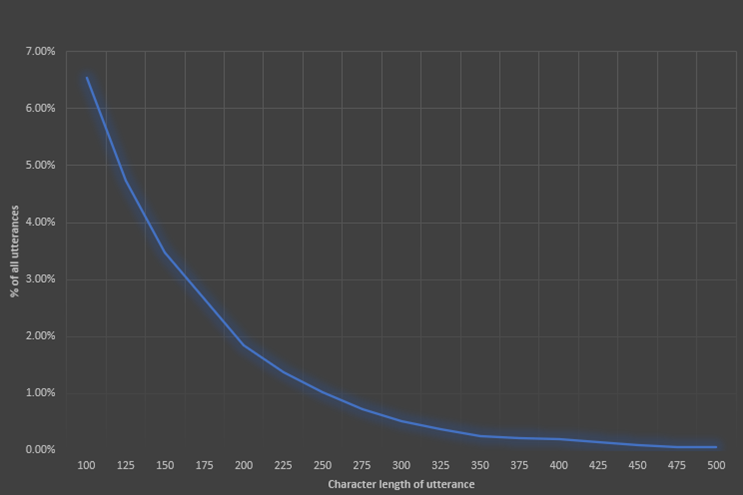

In a recent review, we saw that whilst long utterances occurred regularly, they made up a small percentage across all the conversations. In our sample of 5000 conversations, about 1% of utterances were longer than 250 characters, and that quickly tailed off.

How prevalent are long user utterances?

Long utterances are challenging for bots

Before we look at the methods and mitigations surrounding long utterances, let’s address why they’re even an issue. From the bots’ point of view isn’t getting lots of keywords helpful to direct that customer to the help they seek? Well, whilst that’s partially true, what can happen is that there are so many different intents wrapped up in a single long utterance, that it can’t discern what’s important. Longer inputs contain more sentences, and input processors tend to process one long string of text in multi-sentence utterances. The bot may conclude that 3 or more intents might be relevant, or reply with totally the wrong answer, or no answer at all due to lack of confidence.

This is a frustrating outcome for both parties in the conversation. We need to look at it from the customer’s point of view, of course. In a customer service world, the majority of long utterances describe a series of events that have led up to the need to contact customer services. So, they are frequently unhappy or frustrated from the get-go. They’ve already invested time writing out a comprehensive timeline of their particular issue and now the bot won’t even understand them. It’s an infuriating experience.

We’ve also seen conversations where the customer has pasted in a marketing email from the company asking what part of it means. Bots will also hear about superfluous details such as the health of the user’s pets or that they’ve just got back from a trip abroad. The extra detail just serves to confuse the bot further.

However, this is how people talk and get things done in real life. We’ve all been there in a queue while the person in front of us regales the cashier with the trouble they had in catching the train that morning. One of the main advantages of using bots is that there is no queue of course!

Humans are brilliant at identifying the underlying importance and inference in a lengthy message. But, even the most experienced customer service agents may need to confirm the complaint or ask disambiguation questions, such as ‘so, did you want a refund or a replacement item?’ They might even say ‘Sorry, I don’t totally understand what’s happened – are you saying your package got delivered to the wrong house?’, and that’s perfectly ok in real life. We mustn’t think the bot has to understand everyone, with any problem, every time. What a person definitely wouldn’t say is ‘Can you say that again using fewer words?’.

Approaches for deterring long utterances

One paradigm of good conversation design is that people shouldn’t have to learn how to interact with a bot – and that’s true. The bot should really learn how to interact with people. We also need to remember that for some customers, it’ll be their first time using a bot and they aren’t sure what to do or say.

So, how do we mitigate against the long utterances that the bot will hear?

Remind people they’re talking to a bot early on

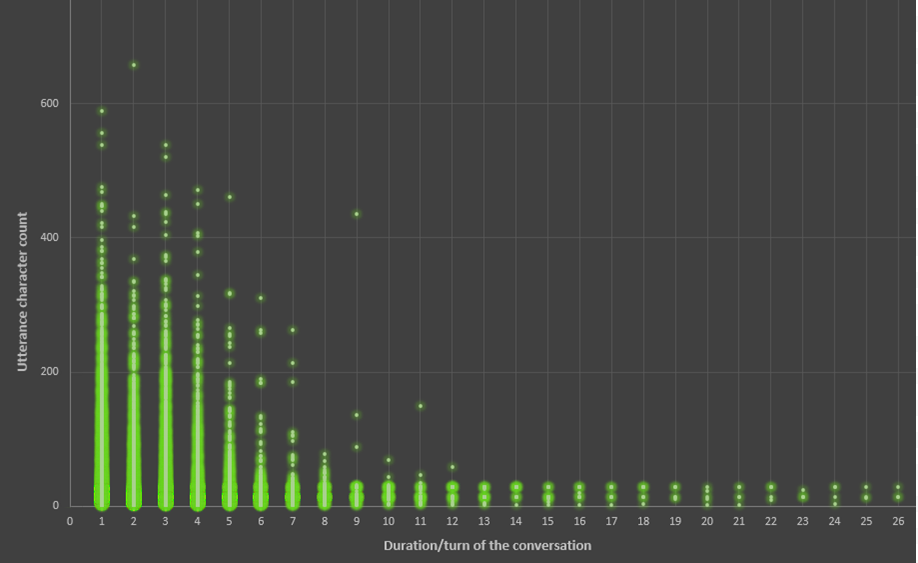

What we’ve seen from our analysis is that long user utterances frequently occur at the very beginning of the conversation, or where the bot asks an open-ended question asking for more details about an issue.

How does utterance length change during the course of the conversation?

Chatbot and live chat windows generally look the same, and often take place in the same interface. Bots may have human names and maybe even a little avatar. People are busy and may not realise it’s a bot at all.

Impose a character limit on how much they can type

We don’t think this is a good approach initially. The customer may not have got to the important detail by the time the character limit is reached and find themselves forced to submit that to the bot, probably getting a non-helpful response, and then send another message to which the bot is unlikely to have sufficient contextual understanding to respond usefully!

Character limits often go hand-in-hand with a visible character counter, but this may actually encourage users to write more and is therefore counter-productive.

Another factor to consider is that they may end up chatting with a human through the same interface, and it may make sense to allow longer messages in those situations.

Encourage shorter responses wherever possible

Using friendly phrases to prompt them to write less helps to guide the user. Using ‘quick reply’ buttons can also be helpful in a chatbot scenario.

Show disambiguation options

If the bot cannot discern between 3 likely intents, presenting them all with a friendly disambiguation message can help – just as a human might do in real life.

If these options can also relate to what is known about the user, all the better. Do they already have an open complaint, for example? Their long utterance could well be extra information relating to that.

Show likely intentions up-front

In the greeting message, we can pre-empt likely issues by examining the current state of the customers’ account, if known. For example, was their package delayed or was there a recent payment issue? Presenting some likely options with well-designed flows supporting those options, prevents them from typing out a long initial explanation of something that just happened to them.

Handover to a human agent

This isn’t always an option of course, but when someone invests a lot of time telling the bot about an issue it’s likely to be complex and therefore needs a human brain to untangle what’s occurred.

We should also embrace the idea that the customer themselves doesn’t know what they want or what the next steps should be, and that may be best discussed with a human.

In summary

People like to communicate with chatbots in different ways and although the bot should try and accommodate everyone, sometimes it simply suffers from ‘too much information’ and isn’t as accurate as it could be. Our approach is to subtly inform and nudge the user into giving shorter responses where possible, but without patronising or frustrating them further. The strategy doesn’t produce overnight results on its own. For many, chatbots represent a new way to communicate and it may be some time before humans work out the best way to get the most out of the experience. Bots should therefore cater for long utterances the best they can.

If we look at the problem from a different perspective, it’s actually a testament to the perceived capabilities of CAI that users feel they can interact in a way that feels natural to them.

(Photo credit Karsten Winegeart on Unsplash)